Израиль мүсіні - Israeli sculpture

Израиль мүсіні тағайындайды мүсін өндірілген Израиль жері 1906 жылдан бастап «Безелель атындағы өнер-қолданбалы өнер мектебі «(бүгінде Безелель атындағы Өнер және Дизайн академиясы деп аталған) құрылды. Израиль мүсіндерінің кристалдану процесі әр кезеңде халықаралық мүсіннің әсерінде болды. Израиль мүсінінің алғашқы кезеңінде оның маңызды мүсіншілерінің көпшілігі елге қоныс аударушылар болды. Израиль және олардың өнері а синтез еуропалық мүсіннің Израиль жерінде, кейінірек мемлекетінде ұлттық көркемдік сәйкестіліктің даму жолымен әсерін Израиль.

Жергілікті мүсін стилін дамытуға күш-жігер 30-шы жылдардың аяғында басталды, «Кананит «мүсін, ол еуропалық мүсіннің әсерін шығыстан, әсіресе, алынған мотивтермен біріктірді Месопотамия. Бұл мотивтер ұлттық тұрғыдан тұжырымдалды және сионизм мен отан топырағы арасындағы байланысты ұсынуға тырысты. 20 ғасырдың ортасында Израильде «Жаңа көкжиектер» қозғалысының әсерімен гүлденіп, әмбебап тілде сөйлейтін мүсіндерді ұсынуға тырысқан дерексіз мүсіннің ұмтылыстарына қарамастан, олардың өнеріне бұрынғы «кананиттің» көптеген элементтері кірді. «мүсін. 1970 жылдары көптеген жаңа элементтер халықаралық әсер етуімен израильдік өнер мен мүсінге өз жолын тапты тұжырымдамалық өнер. Бұл техникалар мүсіннің анықтамасын айтарлықтай өзгертті. Сонымен қатар, бұл әдістер осы уақытқа дейін израильдік мүсіндерде аз болып келген саяси және әлеуметтік наразылықты білдіруге ықпал етті.

Тарих

«Израиль» мүсінін жасау үшін 19 ғасырдағы израильдік дереккөздерді іздеу әрекеті екі тұрғыдан алғанда проблемалы болып табылады. Біріншіден, суретшілерге де, Израиль жеріндегі еврей қоғамына да болашақта израильдік мүсіннің дамуына ілесетін ұлттық сионистік мотивтер жетіспеді. Бұл, әрине, сол кезеңдегі еврей емес суретшілерге де қатысты. Екіншіден, өнер тарихын зерттеу Израиль жеріндегі еврей қауымдастықтары арасында немесе сол кезеңдегі араб немесе христиан тұрғындары арасында мүсін жасау дәстүрін таба алмады. Ицхак Эйнхорн, Хавива Пелед және Йона Фишер жүргізген зерттеулерде осы кезеңдегі қажылыққа барушылар үшін, демек экспорт үшін де, жергілікті үшін де жасалынған діни (еврей және христиан) сипаттағы сәндік өнерді қамтитын көркемдік дәстүрлер анықталды. қажеттіліктер. Бұл нысандарға көбінесе графика өнері дәстүрінен алынған мотивтермен безендірілген таблеткалар, бедерлі сабындар, мөрлер және т.б.[1]

Оның «Израиль мүсінінің қайнарлары» мақаласында[2] Гидеон Офрат израильдік мүсіннің басталуын 1906 жылы Безелел мектебінің негізін қалаған деп анықтады. Сонымен бірге, ол мүсіннің бірыңғай суретін ұсынуға тырысуда проблема тапты. Бұған себептер европалықтардың израильдік мүсінге әсер етуінің әртүрлілігі және Израильдегі мүсіншілердің салыстырмалы түрде аз болуы болды, олардың көпшілігі Еуропада ұзақ уақыт жұмыс істеді.

Сонымен қатар, тіпті Безелельде - мүсінші негізін қалаған өнер мектебінде - мүсін кіші өнер болып саналды, ал ондағы жұмыстар кескіндеме өнері мен графика мен дизайн қолөнеріне шоғырланды. 1935 жылы құрылған «Жаңа Безелелде» де мүсін маңызды орын алмады. Жаңа мектепте мүсін бөлімі құрылғандығы рас болса да, ол бір жылдан кейін жабылды, өйткені ол студенттерге дербес бөлім ретінде емес, көлемді дизайнды үйренуге көмектесетін құрал ретінде қарастырылды. Оның орнына керамика бөлімі[3] ашылды және гүлденді. Осы жылдары Безелел мұражайында да, Тель-Авив музейінде де жеке мүсіншілердің көрмелері болды, бірақ бұл ерекшеліктер болды және үш өлшемді өнерге деген жалпы қатынасты білдірмейді. Көркем мекеменің мүсінге деген екіұшты көзқарасы әр түрлі инкарнацияларда, 1960 жж.

Израиль жеріндегі ерте мүсін

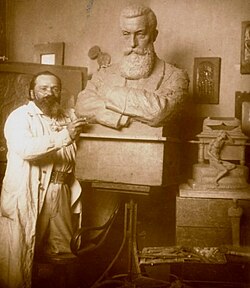

Израиль жеріндегі және жалпы Израиль өнеріндегі мүсіннің басталуы, әдетте, 1906 жылы, Иерусалимдегі Безелел атындағы өнер-қолданбалы өнер мектебінің құрылған жылы деп белгіленеді. Борис Шатц. Парижде мүсін өнерімен айналысқан Шатц Марк Антокольский, ол Иерусалимге келгенде белгілі мүсінші болған. Ол академиялық стильде еврей пәндерінің рельефтік портреттерін салуға маманданған.

Шатцтың жұмысы жаңа еврей-сионистік сәйкестікті орнатуға тырысты, ол мұны европалық христиан мәдениетінен шыққан Інжілдегі фигураларды қолдану арқылы білдірді. Мысалы, оның «Матай Гасмоний» (1894) еңбегінде еврей ұлттық батыры бейнеленген Маттатиас бен Йоханан қылышын ұстап, аяғын грек солдатының денесіне тіреді. Мұндай бейнелеу «Зұлымдықты жеңу» идеялық тақырыбымен байланысты, мысалы, XV ғасырдағы мүсіндегі Персей фигурасында.[4] Еврейлердің қоныстану көшбасшылары үшін жасалған Шатцтың бірқатар ескерткіш тақталарының өзі Арс Ново дәстүріндегі сипаттама дәстүрімен үйлестірілген классикалық өнерден алынған. Классикалық және Ренессанс өнері Шатцты Безелелге тапсырыс берген мүсіндердің көшірмелерінен де көруге болады, ол оны Безелел мұражайында мектеп оқушылары үшін идеалды мүсіннің мысалдары ретінде көрсетті. Бұл мүсіндерге «Дэвид »(1473–1475) және« Дельфинмен путто »(1470) Андреа дель Верроккио.[5]

Безелельдегі зерттеулер кескіндемені, сурет салуды және дизайнды дамытуға бейім болды, нәтижесінде үш өлшемді мүсіннің саны шектеулі болды. Мектепте ашылған бірнеше шеберханалардың ішінде біреуі болды ағаш ою онда әр түрлі сионистік және еврей көшбасшыларының рельефтері, қолданбалы өнердегі декоративті дизайн шеберханалары, мысты жұқа қаңылтырға соғу, асыл тастарды орнату және т.б. сияқты әдістер қолданылған. піл сүйегі қолданбалы өнерге де баса назар аударған дизайн ашылды.[6] Қызмет барысында дербес жұмыс істейтін шеберханалар қосылды. Шатц 1924 жылы маусымда шығарған жадында Безелельдің барлық негізгі қызмет салаларын атап өтті, олардың ішінде ең алдымен «Еврей легионы» және ағаш кесу шеберханасы аясында мектеп оқушылары негізін қалаған тас мүсін болды.[7]

Шатцтан басқа Иерусалимде Безелелдің алғашқы күндерінде мүсін саласында жұмыс істейтін бірнеше суретшілер болған. 1912 жылы Зеев Рабан Шатцтың шақыруы бойынша Израиль жеріне қоныс аударды және Безелелде мүсін жасау, қаңылтырмен жұмыс жасау және анатомия бойынша нұсқаушы болды. Рабан Мюнхендегі Бейнелеу өнері академиясында мүсін өнерімен айналысқан, кейінірек Ecole des Beaux-Arts жылы Париж және Корольдік бейнелеу өнері академиясы жылы Антверпен, Бельгия. Рабан өзінің белгілі графикалық жұмыстарынан басқа Йемендік еврейлер ретінде бейнеленген Інжіл фигураларының «Эли мен Самуил» (1914) терракоталық мүсіншесі сияқты академиялық «Шығыс» стилінде бейнелі мүсіндер мен рельефтер жасады. Рабанның ең маңызды жұмысы зергерлік бұйымдар мен басқа да сәндік заттарға арналған бедерге бағытталған.[8]

Безелелдің басқа нұсқаушылары да шынайы академиялық стильде мүсіндер жасады. Элиезер Стрих мысалы, еврей қонысында адамдардың бюсттерін жасады. Тағы бір суретші, Ицхак Сиркин ағаштан және тастан қашалған портреттер.

Осы кезеңдегі Израиль мүсініне негізгі үлес Безалил шеңберінен тыс жұмыс істеген Авраам Мельникоффқа қосылуы мүмкін. Мельникофф өзінің алғашқы туындысын 1919 жылы Израиль жеріне келгеннен кейін, Израильде жасады.Еврей легионы 1930-шы жылдарға дейін Мельникофф тастың әр түрлі түріндегі мүсіндер сериясын шығарды, көбіне портреттер салынды. терракота және тастан қашалған стильді бейнелер. Оның маңызды жұмыстарының қатарында еврейлердің жеке басын оятуды бейнелейтін символдық мүсіндер тобы бар, мысалы «Оянған Иуда» (1925) немесе ескерткіш ескерткіштер Ахад Хаам (1928) және Макс Нордау (1928). Сонымен қатар, Мельникофф Израиль жеріндегі Суретшілер көрмесінде өзінің туындыларының тұсаукесерлерін басқарды Дәуіт мұнарасы.

«Арсылдаған арыстан» ескерткіші (1928–1932) - бұл үрдістің жалғасы, бірақ бұл мүсін сол кезеңдегі еврей жұртшылығы қабылдаған тәсілмен ерекшеленеді. Мельникоффтың өзі ескерткіш тұрғызуға бастамашы болды және жобаны қаржыландыруға Хистадрут ха-Клалит, Еврейлер ұлттық кеңесі және Альфред Мон (Лорд Мелчетт). Монументалды бейнесі арыстан, гранитпен мүсінделген, Месопотамия өнерімен үйлескен қарабайыр өнердің әсерінен 7-8 ғ.ғ.[9] Стиль ең алдымен фигураның анатомиялық дизайнында көрінеді.

20-шы жылдардың аяғы мен 1930-шы жылдардың басында Израиль жерінде жұмыс жасай бастаған мүсіншілер әр түрлі әсер мен стильдерді көрсетті. Олардың арасында Безелель мектебінің ілімін ұстанған бірнеше адам болды, ал басқалары Еуропада оқығаннан кейін келіп, алғашқы француз модернизмінің өнерге әсерін немесе экспрессионизмнің, әсіресе оның неміс түріндегі әсерін алып келді.

Безелелдің студенттері болған мүсіншілердің арасында Аарон Прайвер ерекшелену. Прайвер 1926 жылы Израиль жеріне келіп, Мельникоффпен мүсін өнерін оқи бастады. Оның жұмысында реализмге бейімділік пен архаикалық немесе орташа қарабайыр стиль үйлесімі көрсетілген. Оның 1930 жылдардағы әйел фигуралары дөңгелек сызықтармен және бет-әлпетімен безендірілген. Тағы бір оқушы, Начум Гутман, суреттерімен және суреттерімен жақсы танымал, саяхаттады Вена 1920 жылы, кейінірек барды Берлин және Париж Мұнда ол мүсін және баспа ісін зерттеп, экспрессионизм іздерін және оның субъектілерін бейнелеуде «қарабайыр» стильге бейімділікті көрсететін мүсіндерді аз көлемде шығарды.

Шығармалары Дэвид Озеранский (Агам) -ның сәндік дәстүрін жалғастырды Зеев Рабан. Озеранский тіпті Иерусалимдегі YMCA ғимаратына арнап жасаған Рабан мүсіндік декорациясында жұмысшы болып жұмыс істеді. Озеранскийдің осы кезеңдегі ең маңызды жұмысы - «Он тайпа» (1932) - Израиль жерінің тарихымен байланысты он мәдениетті символдық тұрғыдан сипаттайтын он шаршы декоративті тақтайшалар тобы. Осы кезеңде Озеранцкийдің тағы бір туындысы Иерусалимдегі Генерал ғимаратының басында тұрған «Арыстан» (1935) болды.[10]

Ол ешқашан мекемеде оқымаса да, жұмыс Дэвид Полус Шатц Безелелде тұжырымдаған еврей академиясына бекітілді. Полус еңбек корпусында тас қалаушы болғаннан кейін мүсіндей бастады. Оның алғашқы маңызды жұмысы - «Қойшы Давидтің» мүсіні (1936–1938) Рамат Дэвид. Оның монументалды жұмысында 1940 »Александр Зейд мемориалы «, ол» Шейх Абрейкте «бетонмен құйылған және жанында орналасқан Бейт Шеарим Ұлттық саябақ, Полус «Күзетші» деп аталатын адамды Джезрел алқабына қарайтын шабандоз ретінде бейнелейді. 1940 жылы Полус ескерткіштің түбіне архаикалық-символикалық стильде екі тақтайша қойды, олардың тақырыптары «қалың» және «бақташы» болды.[11] Бас мүсіннің стилі шынайы болғанымен, оның затын дәріптеуге және оның жермен байланысын баса көрсетуге тырысқаны белгілі болды.

1910 жылы мүсінші Чана Орлофф Израиль жерінен Францияға қоныс аударып, оқуларын бастады École Nationale des Art Décoratifs. Оқу кезеңінен басталған оның жұмысы оның сол кездегі француз өнерімен байланысын баса көрсетеді. Уақыт өте келе өз жұмысында модерация жасаған кубистік мүсіннің әсері ерекше көрінеді. Оның мүсіндері, көбінесе тас пен ағашқа қашалған адам бейнелері, геометриялық кеңістіктер мен ағын сызықтармен жасалған. Оның жұмысының едәуір бөлігі француз қоғамы қайраткерлерінің мүсіндік портреттеріне арналған.[12] Оның Израиль жерімен байланысы, Орлофф Тель-Авив мұражайындағы жұмыстарының көрмесі арқылы сақталды.[13]

Кубизмнің әсері мол болған тағы бір мүсінші - Зеев Бен Цви. 1928 жылы Безалельдегі оқудан кейін Бен Зви Парижге оқуға кетті. Қайтып оралғаннан кейін, ол Безелелде және «Жаңа Безелелде» мүсін бойынша нұсқаушы болып қысқа уақыт қызмет етті. 1932 жылы оның алғашқы көрмесі Безелельдің ұлттық көне мұражайында өтті, ал бір жылдан кейін ол Тель-Авив мұражайында өз жұмыстарының көрмесін қойды. Оның «Пионер» мүсіні 1934 жылы Тель-Авивтегі Шығыс жәрмеңкесінде қойылды. Бен Цвидің шығармашылығында, Орлоффтағы сияқты, кубистердің тілі, оның мүсіндерін жасаған тіл, реализмнен бас тартпады және сол қалада қалды. дәстүрлі мүсіннің шекаралары.[14]

Француз реализмінің әсері ХХ ғасырдың басындағы француз мүсіншілерінің шынайы тенденциясы әсер еткен израильдік суретшілер тобынан да көрінеді. Огюст Роден, Aristide Maillol Олардың мазмұны мен стилінің символдық багажы израильдік суретшілердің жұмыстарында да көрінді, мысалы Мозес Штерншусс, Рафаэль Чамизер, Моше Зифер, Джозеф Констант (Константиновский), және Дов Фейгин, олардың көпшілігі Францияда мүсін өнерін оқыды.

Суретшілердің осы тобының бірі - Батя Лишанский - Безелелде кескіндемені оқып, Парижде мүсін курстарынан өткен. École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Ол Израильге оралғаннан кейін, бейнелі және мәнерлі мүсін жасады, ол Роденнің мүсіндерінің тәндігіне баса назар аударған айқын әсерін көрсетті. Лишанский жасаған ескерткіштер сериясы, оның біріншісі - «Еңбек және қорғаныс» (1929). Эфраим Чисик - Хулда фермасы үшін шайқаста қайтыс болған (бүгін, Киббутц) Хульда ) - сол кезеңдегі сионистік утопияның көрінісі ретінде: жерді сатып алу мен отанды қорғаудың үйлесімі.

Неміс өнерінің және әсіресе неміс экспрессионизмінің әсері әр түрлі қалаларда және Венада өнер бойынша білім алғаннан кейін Израиль жеріне келген суретшілер тобынан көрінеді. Сияқты суретшілер Джейкоб Бранденбург, Трюд Хайм, және Лили Гомпретц-Битус Джордж Лешницер импрессионизм мен қалыпты экспрессионизм арасында ауытқитын стильде жасалған, ең алдымен, портреттік мүсін жасады. Сол топтың суретшілері арасында Рудольф (Руди) Леман, 1930 жылдары өзі ашқан студияда көркемөнерден сабақ бере бастайды. Леманн мүсіндер мен ағаш кескіндерін жануарлар мүсіндеріне маманданған Л.Фюрдермайер деген неміспен бірге оқыды. Леман жасаған фигуралар мүсін жасалған материал мен мүсіншінің онымен жұмыс істеу тәсілін баса көрсететін дененің өрескел дизайнындағы экспрессионизмнің әсерін көрсетті. Леманның оның жұмысын жалпы бағалауына қарамастан, израильдік көптеген суретшілерге тас пен ағаштан жасалған классикалық мүсін әдістерін оқытушы ретінде бірінші кезекте тұрған.

Кананит абстрактілі, 1939–1967 жж

1930 жылдардың аяғында «Қанахандықтар «- негізінен әдеби сипаттағы кең мүсіндік қозғалыс Израильде құрылды. Бұл топ христиан дәуіріне дейінгі екінші мыңжылдықта Израиль жерінде өмір сүрген алғашқы адамдар мен еврей халқы арасында тікелей сызық құруға тырысты. 20 ғасырда Израиль жері, сонымен бірге өзін еврей дәстүрінен бөліп алатын жаңа мәдениетті құруға ұмтылды.Бұл қозғалыспен тығыз байланыста болған суретші мүсінші болды. Итжак Данцигер, өнерді оқығаннан кейін 1938 жылы Израиль жеріне оралды Англия. Данцигердің «канааниттік» өнері ұсынған жаңа ұлтшылдық, анти-еуропалық және шығыс нәзіктік пен экзотикаға толы ұлтшылдық Израиль жеріндегі еврей қауымдастығында тұратын адамдардың көпшілігінің көзқарасын көрсетті. «Данцигер ұрпағының арманы», Амос Кейнан Данцигер қайтыс болғаннан кейін жазды: «Израиль жерімен және жермен бірігу, осы жерден шыққан және біз болып табылатын белгілі белгілермен белгілі бір бейнені жасау және тарихта біз болған ерекше заттың мөрін басу .[15] Суретшілер ұлтшылдықтан бөлек, сол кезеңдегі британдық мүсін рухында символдық экспрессионизмді бейнелейтін мүсін жасады.

Тель-Авивте Данцигер әкесінің ауруханасының ауласында мүсіндер студиясын құрды және сол жерде ол жас мүсіншілерді сынап, оқытты. Бенджамин Таммуз, Kosso Eloul, Ехиел Шеми, Мордехай Гумпель, және басқалар.[16] Данцигердің тәрбиеленушілерінен басқа, студия басқа саладағы суретшілердің жиналатын орнына айналды. Данцигер осы студияда өзінің алғашқы маңызды шығармаларын - «Нимрод» (1939) және «Шебазия» (1939) жасады.

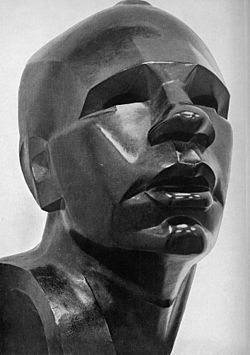

Ол алғаш рет көрсетілген сәттен бастап «Нимрод» мүсіні Эрец Израиль мәдениетінің дауларының орталығына айналды; Данцигер бұл мүсінде фигурасын ұсынды Намруд, библиялық аңшы, жалаңаш және сүндеттелмеген арық жас кезінде, денесіне қылышын қысып, иығында сұңқар. Мүсіннің формасы Ассирия, Египет және Грек мәдениеттерінің алғашқы өнерін еске түсірді және рухы жағынан осы кезеңдегі еуропалық мүсінге ұқсас болды. Оның түрінде мүсіннің ерекше үйлесімі көрсетілген гомоэротикалық сұлулық пен пұтқа табынушылық. Бұл үйлесімділік еврейлер тұратын елді мекендегі діни қауымдастықтың сынында болды. Сонымен бірге басқа дауыстар оны «жаңа еврей адамы» үшін үлгі деп жариялады. 1942 жылы «ХаБокер» газетінде «Нимрод жай мүсін емес, ол біздің тәніміздің еті, біздің рухымыздың рухы. Бұл маңызды оқиға және ескерткіш. Бұл - тапқырлықтың және батылдық, монументалдылық, бүкіл ұрпақты сипаттайтын жас бүлік ... Нимрод мәңгі жас болады ».[17]

Мүсіннің алғашқы көрсетілімі «Эресц Израиль жастарының жалпы көрмесінде» Хабима театры 1942 жылдың мамырында[18] «канааниттер» қозғалысына қатысты тұрақты дәлелдер келтірді. Көрме болғандықтан, Йонатан Ратош, қозғалыстың негізін қалаушы, онымен байланысып, онымен кездесуді сұрады. «Нимродқа» және канахандықтарға қарсы сын тек жоғарыда айтылғандай пұтқа табынушылар мен пұтқа табынушыларға қарсы наразылық білдірген діни элементтерден ғана емес, сонымен бірге «еврейлердің» бәрін алып тастауды айыптаған зайырлы сыншылардан келіп түсті. «Нимрод» айтарлықтай дәрежеде бұрыннан басталған даудың ортасында аяқталды.

Данцигер кейінірек «Нимродқа» Израиль мәдениетінің үлгісі ретінде күмәнданғанына қарамастан, көптеген басқа суретшілер мүсінге канахандық тәсілді қабылдады. «Қарабайыр» стильдегі пұттар мен фигуралардың бейнелері Израиль өнерінде 1970 жылдарға дейін пайда болды. Сонымен қатар, бұл топтың әсерін «Жаңа көкжиектер» тобының жұмысында айтарлықтай байқауға болады, олардың мүшелерінің көпшілігі өздерінің өнер мансабында қананит стилімен тәжірибе жасаған.

«Жаңа көкжиектер» тобы

1948 жылы «деп аталатын қозғалысЖаңа көкжиектер «(» Офаким Хадашим «) құрылды. Ол еуропалық модернизм құндылықтарымен, әсіресе абстрактілі өнермен анықталды. Kosso Eloul, Моше Штерншусс, және Дов Фейгин қозғалыстың негізін қалаушылар тобына тағайындалды, кейінірек оларға басқа мүсіншілер қосылды. Израильдік мүсіншілер азшылық ретінде олардың қозғалыстағы санының аздығынан ғана емес, ең алдымен қозғалыс көшбасшыларының көзқарасы бойынша кескіндеме құралының үстемдігінен қабылданды Джозеф Зарицкий. Топ мүшелерінің мүсіндерінің көпшілігі «таза» дерексіз мүсін болмағанына қарамастан, олар абстрактілі өнер мен метафизикалық символизм элементтерін қамтыды. Абстрактілі емес өнер көне және маңызды емес деп қабылданды. Штерншусс, мысалы, бейнелеу элементтерін өз өнеріне қоспау үшін топ мүшелеріне жасалған қысымды сипаттады. Бұл топ мүшелері «абстракция жеңісі» жылы деп санайтын, 1959 жылы басталған ұзақ күрес болды.[19] және шыңына 1960 жылдардың ортасында жетті. Стерншусс тіпті суретшілердің біреуі жалпыға бірдей қабылданғаннан гөрі авангардтық мүсінді көрсеткісі келген оқиға туралы әңгіме айтты. Бірақ оның басы бар еді, соған байланысты басқарма мүшелерінің бірі осы мәселе бойынша оған қарсы жауап берді.[20]

Гидеон Офрат топ туралы очеркінде «Жаңа көкжиектердің» кескіндемесі мен мүсіні мен «кананиттер» өнері арасында мықты байланыс тапты.[21] Топ мүшелері көрсеткен «халықаралық» реңкке қарамастан, олардың көптеген жұмыстары Израиль пейзажының мифологиялық бейнесін көрсетті. Мысалы, 1962 жылы желтоқсанда Коссо Элоул мүсін бойынша халықаралық симпозиум ұйымдастырды Мицпе Рамон. Бұл іс-шара мүсіндердің Израиль ландшафтына, атап айтқанда қаңырап қалған шөлді ландшафтқа деген қызығушылығының артуының мысалы болды. Ландшафт, бір жағынан, көптеген ескерткіштер мен мемориалдық мүсіндер жасау үшін ойлау процесінің негізі ретінде қабылданды. Йона Фишер 1960 жылдары өнерге арналған зерттеулерінде мүсіншілердің «шөл сиқырына» деген қызығушылығы табиғатқа деген романтикалық құмарлықтан ғана емес, сонымен қатар Израильге «Мәдениет» ортасын сіңіру әрекетінен туындады деп жорамалдайды. «өркениетке» қарағанда.[22]

Топтың әр мүшесінің шығармашылығына арналған сынақ абстракциямен және пейзажбен басқаша жұмыс жасады. Дов Фейгин мүсінінің абстрактілі табиғатының кристалдануы халықаралық мүсін әсер еткен көркемдік ізденіс процесінің бөлігі болды, әсіресе Хулио Гонсалес, Константин Бранку, және Александр Калдер. Ең маңызды көркемдік өзгеріс 1956 жылы Фейгин металл (темір) мүсінге ауысқан кезде болды.[23] Осы жылдан бастап оның «Құс» және «Ұшу» сияқты жұмыстары динамизм мен қозғалысқа толы композицияларға салынған темір жолақтарды дәнекерлеу арқылы салынды. Кесілген және майысқан мыс немесе темірді пайдаланып, сызықтық мүсіннен жазықтық мүсінге ауысу Фейгин үшін табиғи даму процесі болды, оған әсер еткен шығармалар әсер етті. Пабло Пикассо осыған ұқсас техниканы қолданып жасалған.

Моше Стерншусс Фейгиннен айырмашылығы абстракцияға қарай біртіндеп дамуын көрсетеді. Штерншусаль Безелелде оқуды аяқтағаннан кейін Парижге оқуға кетті. 1934 жылы ол Тель-Авивке оралды және Авни өнер және дизайн институтының негізін қалаушылардың қатарында болды. Стерншусстың сол кезеңдегі мүсіндері академиялық модернизмді көрсетті, бірақ оларда Безелел мектебінің өнерінде сионистік ерекшеліктер болмаса да. 1940 жылдардың ортасынан бастап оның адамдық фигуралары абстракцияға айқын тенденцияны көрсетті, сонымен қатар геометриялық формалардың көбеюі. Осы мүсіндердің алғашқыларының бірі «Би» (1944) болды, ол осы жылы «Нимродтың» жанындағы көрмеге қойылды. Штерншусстың жұмысы ешқашан абстрактілі болмады, бірақ бейнелі емес тәсілдермен адам фигурасымен айналысуды жалғастырды.[24]

Итжак Данцигер 1955 жылы Израильге оралғанда «Жаңа көкжиектерге» қосылып, металлдан мүсіндер жасай бастайды. Ол жасаған мүсіндер стиліне конструктивті өнер әсер етті, ол оның абстрактілі түрінде көрінді. Соған қарамастан, оның мүсіндерінің көп бөлігі жергілікті болды, мысалы, «Хаттин мүйіздері» (1956), Саладиннің крестшілерді жеңген орны, 1187 ж. (1957) немесе Израильдегі «Эйн Геди» (1950 ж.), «Негевтің қойы» (1963) және т.б жерлермен. Бұл үйлесімділік қозғалыстың көптеген суретшілерінің туындыларын сипаттады.[25]

Ечиэль Шеми, сонымен қатар Данцигердің тәрбиеленушілерінің бірі, 1955 жылы металл мүсінге практикалық себеппен көшті. Бұл қозғалыс оның жұмысындағы абстракцияға көшуді жеңілдетті. Дәнекерлеу, дәнекерлеу және жіңішке жолақтарға балға соғу техникасын қолданған оның жұмыстары осы топтан шыққан алғашқы мүсіншілердің бірі болды. 26 «Мифос» (1956) сияқты шығармаларында Шемидің Ол дамытқан «кананиттік» өнерді әлі де байқауға болады, бірақ көп ұзамай ол бейнелеу өнерінің барлық белгілерін шығармасынан алып тастады.

Израильде туылған Рут Царфати Авнидің студиясында мүсінді оның күйеуі болған Мозес Штерншусстан оқыды. Зарфати мен «Жаңа көкжиектер» суретшілері арасындағы стилистикалық және әлеуметтік жақындыққа қарамастан, оның мүсінінде топтың қалған мүшелерінен тәуелсіз реңктер көрсетілген. Бұл ең алдымен оның бейнелі мүсіннің қисық сызықтармен бейнеленуінен көрінеді. Оның «Ол отырады» (1953) мүсінінде Генри Мурдың мүсіні сияқты еуропалық экспрессивтік мүсіннің сызықтық сипаттамаларын қолдана отырып, белгісіз әйел фигурасы бейнеленген. Мүсіннің тағы бір тобы «Сәби қыз» (1959) гротескалық мәнерлі күйде қуыршақ ретінде жасалған балалар мен сәбилер тобын көрсетеді.

Дэвид Паломбо (1920 - 1966) ерте қайтыс болғанға дейін бірқатар қуатты, дерексіз темір мүсіндерді жүзеге асырды.[26] 1960 жылдардағы Паломбо мүсіндерін Холокост туралы «оттың мүсіндік эстетикасы» арқылы бейнелейді деп санауға болады.[27]

Наразылықтың мүсіні

1960 жылдардың басында американдық әсерлер, атап айтқанда абстрактілі экспрессионизм, поп-арт, және кейінірек концептуалды өнер Израиль өнерінде пайда бола бастады. Жаңа көркем формалардан басқа, эстрадалық өнер және концептуалды өнер өздерімен бірге уақыттың саяси және әлеуметтік шындықтарымен тікелей байланысты алып келді. Керісінше, израильдік өнердегі басты тенденция көбінесе израильдік саяси пейзажды талқылауды елемей, жеке және көркемдік мәселелермен айналысуға бағытталды. Өздерін әлеуметтік немесе еврей мәселелерімен айналысатын суретшілерге өнер мекемесі анархист ретінде қарады.[28]

Шығармалары халықаралық көркемдік әсерді ғана емес, сонымен қатар қазіргі саяси мәселелерді шешуге бейімділікті білдіретін алғашқы суретшілердің бірі болды Йигал Тумаркин 1961 жылы Израильге қайтып келді, Берлольд Брехттің жетекшілігімен Берлинер ансамблі театр компаниясының менеджері болған Шығыс Берлиннен Йона Фишер мен Сэм Дубинердің қолдауымен.[29] Оның алғашқы мүсіндері әртүрлі қару-жарақ бөліктерінен жинақталған мәнерлі жиынтық ретінде жасалған. Мысалы, «Мені қанаттарыңның астына ал» (1964–65) мүсіні, мысалы, Тумаркин винтовкалардың бөшкелері ілулі тұрған болат корпусты жасады. Бұл мүсіннен біз ұлтшылдық өлшемі мен лирикасын, тіпті эротикалық өлшемін көретін қоспамыз 1970 жылдары Тумаркиннің саяси өнерінің таңғажайып элементіне айналуы керек еді.[30] Осындай тәсілді оның әйгілі «Ол далада жүрді» (1967) мүсінінен де көруге болады (аттас аттас Моше Шамир әйгілі оқиға), наразылық білдірді имиджі «мифологиялық Сабра»; Тумаркин оның «терісін» шешіп, қаруы мен оқ-дәрі шығып тұрған ішіндегі жыртық ішегін және ішіне күмәнді түрде жатырға ұқсайтын дөңгелек бомба салынған асқазанын ашады. 1970 жылдары Тумаркиннің өнері жаңа материалдарды қамтыды »Жер өнері, «мысалы, кір, ағаш бұтақтары және мата бөліктері. Осылайша, Тумаркин өзінің Израиль қоғамының араб-израиль қақтығысына қатысты біржақты көзқарасы ретінде қараған саяси наразылықтарын күшейтуге тырысты.

Алты күндік соғыстан кейін Израиль өнері Тумаркиннен басқа наразылық білдіре бастады. Сонымен қатар бұл жұмыстар әдеттегідей ағаштан немесе металдан жасалған мүсін туындыларына ұқсамады. Мұның басты себебі АҚШ-та дамыған және израильдік жас суретшілерге әсер еткен авангардтық өнердің әртүрлі түрлерінің әсері болды. Бұл әсер ету рухы әр түрлі өнер салалары арасындағы шекараны және суретшінің қоғамдық және саяси өмірден алшақтауын белсенді белсенді шығармаларға бейімділіктен көрінуі мүмкін. Бұл кезеңдегі мүсін енді дербес көркемдік объект ретінде емес, физикалық және әлеуметтік кеңістіктің өзіндік көрінісі ретінде қабылданды.

Концептуалды өнердегі пейзаж мүсіні

Бұл тенденциялардың тағы бір аспектісі - Израильдің шексіз ландшафтына деген қызығушылықтың артуы. Бұл жұмыстар әсер етті Жер өнері және «Израиль» пейзажы мен «Шығыс» пейзажы арасындағы диалектикалық байланыстың үйлесімі. Ритуалистік және метафизикалық белгілері бар көптеген туындыларда кананиттік суретшілердің немесе мүсіншілердің дамуын немесе тікелей әсерін, «Жаңа көкжиектердің» абстракциясымен қатар, ландшафтпен әр түрлі қатынастарда байқауға болады.

Тұжырымдамалық өнер туын көтерген Израильдегі алғашқы жобалардың бірі Джошуа Нойстейн. 1970 жылы Нойстейн ынтымақтастық жасады Джорджетт Батлле және Герри Маркс «Иерусалим өзенінің жобасы» бойынша. Бұл жоба үшін шөл алқабына орнатылған динамиктер Шығыс Иерусалимде, тау бөктерінде өзеннің ілмектегі дыбыстарын ойнады Абу Тор және Әулие Клер монастыры, және барлық жол Кидрон алқабы. Бұл елестететін өзен тек қана экстерриториялық мұражай атмосферасын құрып қана қоймай, сонымен қатар алты күндік соғыстан кейінгі мессиандық құтқару сезімі туралы ирониялық түрде, Езекиел кітабы (47-тарау) және Зәкәрия кітабы (14 тарау).[31]

Ицхак Данцигер Бірнеше жыл бұрын оның жұмыстары жергілікті ландшафтты бейнелей бастады, концептуалды аспектіні Израильдің Land Art өнерінің ерекше вариациясы ретінде дамытқан стильде көрсетті. Данцигер адам мен оның қоршаған ортасы арасындағы бұзылған қарым-қатынасты жақсарту және жақсарту қажет деп санады. Бұл сенім оны экология мен мәдениетті қалпына келтіретін жобаларды жоспарлауға мәжбүр етті. 1971 жылы Данцигер өзінің «Ілулі табиғат» жобасын The-дағы бірлескен жобада ұсынды Израиль мұражайы. Данцигер жасанды жарық пен суару жүйесін қолданып шөп өсіретін түстер, пластикалық эмульсия, целлюлоза талшықтары және химиялық тыңайтқыштар қоспасы ілулі матадан тұрды. Матаның жанында заманауи индустрияландыру арқылы табиғатты жоюды көрсететін слайдтар көрсетілді. Көрме «өнер» және «табиғат» ретінде бір уақытта болатын экологияны құруды сұрады.[32] Пейзажды «жөндеуді» көркем оқиға ретінде Данцигер өзінің «Нешер карьерін қалпына келтіру» жобасында, солтүстік беткейлерінде жасаған. Кармель тауы. Бұл жоба Данцигердің ынтымақтастығы ретінде құрылды, Зеев Навех эколог және Джозеф Морин топырақ зерттеушісі. Ешқашан аяқталмаған бұл жобада олар карьерде қалған тас сынықтары арасында әр түрлі технологиялық және экологиялық құралдарды қолданып, жаңа орта құруға тырысты. «Табиғатты табиғи күйіне қайтаруға болмайды», - деп дауыстады Данцигер. "A system needs to be found to re-use the nature which has been created as material for an entirely new concept."[33] After the first stage of the project, the attempt at rehabilitation was put on display in 1972 in an exhibit at the Israel Museum.

In 1973 Danziger began to collect material for a book that would document his work. Within the framework of the preparation for the book, he documented places of archaeological and contemporary ritual in Israel, places which had become the sources of inspiration for his work. Кітап, Makom (in.) Еврей - орын), was published in 1982, after Danziger's death, and presented photographs of these places along with Danziger's sculptures, exercises in design, sketches of his works and ecological ideas, displayed as "sculpture" with the values of abstract art, such as collecting rainwater, etc. One of the places documented in the book is Bustan Hayat [could not confirm English spelling-sl ] at Nachal Siach in Haifa, which was built by Aziz Hayat in 1936. Within the framework of classes he gave at the Technion, Danziger conducted experiments in design with his students, involving them also with the care and upkeep of the Bustan.

In 1977 a planting ceremony was conducted in the Голан биіктігі for 350 Oak saplings, being planted as a memorial to the fallen soldiers of the Egoz Unit. Danziger, who was serving as a judge in "the competition for the planning and implementation of the memorial to the Northern Commando Unit," suggested that instead of a memorial sculpture, they put their emphasis on the landscape itself, and on a site that would be different from the usual memorial. ”We felt that any vertical structure, even the most impressive, could not compete with the mountain range itself. When we started climbing up to the site, we discovered that the rocks, that looked from a distance like texture, had a personality all of their own up close."[34] This perception derived from research in Bedouin and Palestinian ritual sites in the Land of Israel, sites in which the trees serve both as a symbol next to the graves of saints and as a ritual focus, "on which they hang colorful shiny blue and green fabrics from the oaks [...] People go out to hang these fabrics because of a spiritual need, they go out to make a wish."[35]

In 1972 group of young artists who were in touch with Danziger and influenced by his ideas created a group of activities that became known as "Metzer-Messer" in the area between Киббутц Metzer and the Arab village Мейзер in the north west section of the Shomron. Миха Ульман, with the help of youth from both the kibbutz and the village, dug a hole in each of the communities and implemented an exchange of symbolic red soil between them. Moshe Gershuni called a meeting of the kibbutz members and handed out the soil of Kibbutz Metzer to them there, and Avital Geva created in the area between the two communities an improvised library of books recycled from Amnir Recycling Industries.[36]

Another artist influenced by Danziger's ideas was Йигал Тумаркин, who at the end of the 1970s, created a series of works entitled, "Definitions of Olive Trees and Oaks," in which he created temporary sculpture around trees. Like Danziger, Tumarkin also related in these works to the life forms of popular culture, particularly in Arab and Bedouin villages, and created from them a sort of artistic-morphological language, using "impoverished" bricolage methods. Some of the works related not only to coexistence and peace, but also to the larger Israeli political picture. In works such as "Earth Crucifixion" (1981) and "Bedouin Crucifixion" (1982), Tumarkin referred to the ejection of Palestinians and Bedouins from their lands, and created "crucifixion pillars" for these lands.[37]

Another group that operated in a similar spirit, while at the same time emphasizing Jewish metaphysics, was the group known as the "Leviathians," presided over by Avraham Ofek, Michail Grobman, and Shmuel Ackerman. The group combined conceptual art and "land art" with Jewish symbolism. Of the three of them, Avraham Ofek had the deepest interest in sculpture and its relationship to religious symbolism and images. In one series of his works Ofek used mirrors to project Hebrew letters, words with religious or cabbalistic significance, and other images onto soil or man-made structures. In his work "Letters of Light" (1979), for example, the letters were projected onto people and fabrics and the soil of the Judean Desert. In another work Ofek screened the words "America," "Africa," and "Green card" on the walls of the Tel Hai courtyard during a symposium on sculpture.[38]

Абстрактілі мүсін

At the beginning of the 1960s Менаше Кадишман arrived on the scene of abstract sculpture while he was studying in Лондон. The artistic style he developed in those years was heavily influenced by English art of this period, such as the works of Anthony Caro, who was one of his teachers. At the same time his work was permeated by the relationship between landscape and ritual objects, like Danziger and other Israeli sculptors. During his stay in Europe, Kadishman created a number of totemic images of people, gates, and altars of a talismanic and primitive nature.[39] Some of these works, such as "Suspense" (1966), or "Uprise" (1967–1976), developed into pure geometric figures.

At the end of this decade, in works such as "Aqueduct" (1968–1970) or "Segments" (1969), Kadishman combined pieces of glass separating chunks of stone with a tension of form between the different parts of the sculpture. With his return to Israel at the beginning of the 1970s, Kadishman began to create works that were clearly in the spirit of "Land Art." One of his main projects was carried out in 1972. In the framework of this project Kadishman painted a square in yellow organic paint on the land of the Monastery of the Cross, in the Valley of the Cross at the foot of the Israel Museum. The work became known as a "monument of global nature, in which the landscape depicted by it is both the subject and the object of the creative process."[40]

Other Israeli artists also created abstract sculptures charged with symbolism. The sculptures of Майкл Гросс created an abstraction of the Israeli landscape, while those of Яаков Агам contained a Jewish theological aspect. His work was also innovative in its attempt to create кинетикалық өнер. Works of his such as "18 Degrees" (1971) not only eroded the boundary between the work and the viewer of the work but also exhorted the viewer to look at the work actively.

Symbolism of a different kind can be seen in the work of Дани Караван. The outdoor sculptures that Karavan created, from "Monument to the Negev Brigade " (1963-1968) to "White Square" (1989) utilized avant-garde European art to create a symbolic abstraction of the Israeli landscape. In Karavan's use of the techniques of modernist, and primarily brutalist, architecture, as in his museum installations, Karavan created a sort of alternative environment to landscapes, redesigning it as a utopia, or as a call for a dialogue with these landscapes.[41]

Micha Ullman continued and developed the concept of nature and the structure of the excavations he carried out on systems of underground structures formulated according to a minimalist aesthetic. These structures, like the work "Third Watch" (1980), which are presented as defense trenches made of dirt, are also presented as the place which housed the beginning of permanent human existence.[42]

Буки Шварц absorbed concepts from conceptual art, primarily of the American variety, during the period that he lived in Нью-Йорк қаласы. Schwartz's work dealt with the way the relationship between the viewer and the work of art is constructed and deconstructed. Ішінде бейнеөнер film "Video Structures" (1978-1980) Schwartz demonstrated the dismantling of the geometric illusion using optical methods, that is, marking an illusory form in space and then dismantling this illusion when the human body is interposed.[43] In sculptures such as "Levitation" (1976) or "Reflection Triangle" (1980), Schwartz dismantled the serious geometry of his sculptures by inserting mirrors that produced the illusion that they were floating in the air, similarly to Kadishman's works in glass.

Representative sculpture of the 1970s

Орындаушылық өнер began to develop in the АҚШ in the 1960s, trickling into Israeli art towards the end of that decade under the auspices of the "Ten Plus " group, led by Раффи Лави және »Үшінші көз " group, under the leadership of Jacques Cathmore.[44] A large number of sculptors took advantage of the possibilities that the techniques of Performance Art opened for them with regard to a critical examination of the space around them. In spite of the fact that many works renounced the need for genuine physical expression, nevertheless the examination they carry out shows the clear way in which the artists related to physical space from the point of view of social, political, and gender issues.

Pinchas Cohen Gan during those years created a number of displays of a political nature. In his work "Touching the Border" (January 7, 1974) iron missiles, with Israeli demographic information written on them, were sent to Israel's border. The missiles were buried at the spot where the Israelis carrying them were arrested. In "Performance in a Refugees Camp in Jericho", which took place on February 10, 1974 in the northeast section of the city of Jericho near Хирбат әл-Мафжар (Hisham's Palace), Cohen created a link between his personal experience as an immigrant and the experience of the Palestinian immigrant, by building a tent and a structure that looked like the sail of a boat, which was also made of fabric. At the same time, Cohen Gan set up a conversation about "Israel 25 Years Hence", in the year 2000, between two refugees, and accompanied by the declaration, "A refugee is a person who cannot return to his homeland."[45]

Another artist, Efrat Natan, created a number of performances dealing with the dissolution of the connection between the viewer and the work of art, at the same time criticizing Israeli militarism after the Six Day War. Among her important works was "Head Sculpture," in which Natan consulted a sort of wooden sculpture which she wore as a kind of mask on her head. Natan wore the sculpture the day after the army's annual military parade in 1973, and walked with it to various central places in Tel Aviv. The form of the mask, in the shape of the letter "T," bore a resemblance to a cross or an airplane and restricted her field of vision."[46]

A blend of political and artistic criticism with poetics can be seen in a number of paintings and installations that Moshe Gershuni created in the 1970s. For Gershuni, who began to be famous during these years as a conceptual sculptor, art and the definition of esthetics was perceived as parallel and inseparable from politics in Israel. Thus, in his work "A Gentle Hand" (1975–1978), Gershuni juxtaposed a newspaper article describing abuse of a Palestinian with a famous love song by Залман Шнейр (called: "All Her Heart She Gave Him" and the first words of which are "A gentle hand", sung to an Arab melody from the days of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914). Gershuni sang like a muezzin into a loudspeaker placed on the roof of the Tel Aviv Museum. In works like these the minimalist and conceptualist ethics served as a tool for criticizing Zionism and Israeli society.[47]

Шығармалары Гедеон Гехтман during this period dealt with the complex relationship between art and the life of the artist, and with the dialectic between artistic representation and real life.[48] In the exhibition "Exposure" (1975), Gechtman described the ritual of shaving his body hair in preparation for heart surgery he had undergone, and used photographed documentation like doctors' letters and x-rays which showed the artificial heart valve implanted in his body. In other works, such as "Brushes" (1974–1975), he uses hair from his head and the heads of family members and attaches it to different kinds of brushes, which he exhibits in wooden boxes, as a kind of box of ruins (a reliquary). These boxes were created according to strict minimalistic esthetic standards.

Another major work of Gechtman's during this period was exhibited in the exhibition entitled "Open Workshop" (1975) at the Израиль мұражайы. The exhibition summarized the sociopolitical "activity" known as "Jewish Work" and, within this framework," Gechtman participated as a construction worker in the building of a new wing of the Museum and lived within the exhibition space. on the construction site. Gechtman also hung obituaries bearing the name "Jewish Work" and a photograph of the homes of Arab workers on the construction site. In spite of the clearly political aspects of this work, its complex relationship to the image of the artist in society is also evident.

1980 және 1990 жылдар

In the 1980s, influences from the international postmodern discourse began to trickle into Israeli art. Particularly important was the influence of philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard, who formulated the concept of the semantic and relative nature of reality in their philosophical writings. The idea that the artistic representation is composed of "simulacra", objects in which the internal relation between the signifier and the signified is not direct, created a feeling that the status of the artistic object in general, and of sculpture in particular, was being undermined.

Gideon Gechtman's work expresses the transition from the conceptual approach of the 1970s to the 1980s, when new strategies were adopted that took real objects (death notices, a hospital, a child's wagon) and gradually converted them into objects of art.[49] The real objects were recreated in various artificial materials. Death notices, for example, were made out of colored neon lights, like those used in advertisements. Other materials Gechtman used in this period were formica and imitation marble, which in themselves emphasized the artificiality of the artistic representation and its non-biographical nature.

Painting Lesson, no 5, 1986

Acrylic and industrial paint on wood; табылған объект

Израиль мұражайы коллекция

During the 1980s, the works of a number of sculptors were known for their use of plywood. The use of this material served to emphasize the way large-scale objects were constructed, often within the tradition of do-it-yourself carpentry. The concept behind this kind of sculpture emphasized the non-heroic nature of a work of art, related to the "Arte Povera" style, which was at the height of its influence during these years. Among the most conspicuous of the artists who first used these methods is Нахум Тевет, who began his career in the 1970s as a sculptor in the minimalist and conceptual style. While in the early 1970s he used a severe, nearly monastic, style in his works, from the beginning of the 1980s he began to construct works that were more and more complex, composed of disassembled parts, built in home-based workshops. The works are described as "a trap configuration, which seduces the eye into penetrating the content [...] but is revealed as a false temptation that blocks the way rather than leading somewhere."[50] The group of sculptors who called themselves "Drawing Lessons," from the middle of the decade, and other works, such as "Ursa Major (with eclipse)" (1984) and "Jemmain" (1986) created a variety of points of view, disorder, and spatial disorientation, which "demonstrate the subject's loss of stability in the postmodernist world."[51]

The sculptures of Drora Domini as well dealt with the construction and deconstruction of structures with a domestic connection. Many of them featured disassembled images of furniture. The abstract structures she built, on a relatively small scale, contained absurd connections between them. Towards the end of the decade Domini began to combine additional images in her works from compositions in the "ars poetica" style.[52]

Another artist who created wooden structures was the sculptor Ысқақ Голомбек. His works from the end of the decade included familiar objects reconstructed from plywood and with their natural proportions distorted. The items he produced had structures one on top of another. Itamar Levy, in his article "High Low Profile" [Rosh katan godol],[53] describes the relationship between the viewer and Golombek's works as an experiment in the separation of the sense of sight from the senses of touching and feeling. The bodies that Golombek describes are dismantled bodies, conducting a protest dialogue against the gaze of the viewer, who aspires to determine one unique, protected, and explainable identity for the work of art. While the form of the object represents a clear identity, the way they are made distances the usefulness of the objects and disrupts the feeling of materiality of the items.

A different kind of construction can be seen in the performances of the Zik Group, which came into being in the middle of the 1980s. Within the framework of its performances, the Group built large-scale wooden sculptures and created ritualistic activities around them, combining a variety of artistic techniques. When the performance ended, they set fire to the sculpture in a public burning ceremony. In the 1990s, in addition to destruction, the group also took began to focus on the transformation of materials and did away with the public burning ceremonies.[54]

Postmodern trends

Another effect of the postmodern approach was the protest against historical and cultural narratives. Art was not yet perceived as ideology, supporting or opposing the discourse on Israeli hegemony, but rather as the basis for a more open and pluralistic discussion of reality. In the era following the "political revolution" which resulted from the 1977 election, this was expressed in the establishment of the "identity discussion," in which parts of society that up to now had not usually been represented in the main Israeli discourse were included.

In the beginning of the 1980s expressions of the trauma of the Холокост began to appear in Israeli society. In the works of the "second generation" there began to appear figures taken from Екінші дүниежүзілік соғыс, combined with an attempt to establish a personal identity as an Israeli and as a Jew. Among the pioneering works were Moshe Gershuni 's installation "Red Sealing/Theatre" (1980) and the works of Haim Maor. These expressions became more and more explicit in the 1990s. A large group of works was created by Игаэль Тумаркин, who combined in his monumental creations dialectical images representing the horrors of the Holocaust with the world of European culture in which it occurred. Суретші Penny Yassour, for example, represented the Holocaust in a series of structures and models in which hints and quotes referring to the war appear. In the work "Screens" (1996), which was displayed at the "Documenta" exhibition, Yassour created a map of German trains in 1938 in the form of a table made out of rubber, as part of an experiment to present the memory and describe the relationship between private and public memory.[55] The other materials Yassour used – metal and wood that created different architectonic spaces – produced an atmosphere of isolation and horror.

Another aspect of raising the memory of the Holocaust to the public consciousness was the focus on the immigrants who came to Israel during the first decades after the founding of the State. These attempts were accompanied by a protest against the image of the Israeli "Сабра " and an emphasis on the feeling of detachment of the immigrants. The sculptor Philip Rentzer presented, in a number of works and installations, the image of the immigrant and the refugee in Israel. His works, constructed from an assemblage of various ready-made materials, show the contrast between the permanence of the domestic and the feeling of impermanence of the immigrant. In his installation "The Box from Nes Ziona" (1998), Rentzer created an Orientalist camel carrying on its back the immigrants' shack of Rentzer's family, represented by skeletons carrying ladders.[56]

In addition to expressions of the Holocaust, a growing expression of the motifs of Jewish art can be seen in Israeli art of the 1990s. In spite of the fact that motifs of this kind could be seen in the past in art of such artists as Arie Aroch, Моше Кастель, және Мордехай Ардон, the works of Israeli artists of the 1990s displayed a more direct relationship to the world of Jewish symbols. One of the most visible of the artists who used these motifs, Белу Симион Файнару used Hebrew letters and other symbols as the basis for the creation of objects with metaphysical-religious significance. In his work "Sham" ("There" in Hebrew) (1996), for example, Fainaru created a closed structure, with windows in the form of the Hebrew letter Шин (ש). In another work, he made a model of a synagogue (1997), with windows in the shape of the letters, Алеф (א) to Зайин (ז) - one to seven - representing the seven days of the creation of the world.[57]

During the 1990s we also begin to see various representations of Жыныс and sexual motifs. Sigal Primor exhibited works that dealt with the image of women in Western culture. In an environmental sculpture she placed on Sderot Chen in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Primor created a replica of furniture made of stainless steel. In this way, the structure points out the gap between personal, private space and public space. In many of Primor's works there is an ironic relationship to the motif of the "bride", as seen Marcel Duchamp's work, "The Glass Door". In her work "The Bride", materials such as cast iron, combined with images using other techniques such as photography, become objects of desire.

In her installation "Dinner Dress (Tales About Dora)" (1997), Tamar Raban turned a dining room table four meters in diameter into a huge crinoline and she organized an installation that took place both on top of and under the dining room table. The public was invited to participate in the meal prepared by chef Tsachi Bukshester and watch what was going on under the table on monitors placed under the transparent glass dinner plates.[58] The installation raises questions about the perceptions of memory and personal identity in a variety of ways. During the performance, Raban would tell stories about "Dora," Raban's mother 's name, with reference to the figure "Dora" – a nickname for Айда Бауэр, one of the historic patients of Зигмунд Фрейд. In the corner of the room was the artist Pnina Reichman, embroidering words and letters in English, such as "all those lost words" and "contaminated memory," and counting in Идиш.[59]

The centrality of the gender discussion in the international cultural and art scene had an influence on Israeli artists. In the video art works of Hila Lulu Lin, the protest against the traditional concepts of women's sexuality stood out. In her work "No More Tears" (1994), Lulu Lin appeared passing an egg yolk back and forth between her hand and her mouth. Other artists sought not only to express in their art homoeroticism and feelings of horror and death, but also to test the social legitimacy of homosexuality and lesbianism in Israel. Among these artists the creative team of Nir Nader және Erez Harodi, and the performance artist Dan Zakheim ерекшелену.

As the world of Israeli art was exposed to the art of the rest of the world, especially from the 1990s, a striving toward the "total visual experience,"[60] expressed in large-scale installations and in the use of theatrical technologies, particularly of video art, can be seen in the works of many Israeli artists. The subject of many of these installations is a critical test of space. Among these artists can be found Ohad Meromi және Михал Ровнер, who creates video installations in which human activities are converted into ornamental designs of texts. In the works of Ури Цайг the use of video to test the activity of the viewer as a critical activity stands out. In "Universal Square" (2006), for example, Tzaig created a video art film in which two football teams compete on a field with two balls. The change in the regular rules created a variety of opportunities for the players to come up with new plays on the space of the football field.

Another well-known artist who creates large-scale installations is Sigalit Landau. Landau creates expressive environments with multiple sculptures laden with political and social allegorical significance. The apocalyptic exhibitions Landau mounted, such as "The Country" (2002) or "Endless Solution" (2005), succeeded in reaching large and varied segments of the population.

Commemorative sculpture

In Israel there are many memorial sculptures whose purpose is to perpetuate the memory of various events in the history of the Jewish people and the State of Israel. Since the memorial sculptures are displayed in public spaces, they tend to serve as an expression of popular art of the period. The first memorial sculpture erected in the Land of Israel was “The Roaring Lion”, which Abraham Melnikoff sculpted in Тель Хай. The large proportions of the statue and the public funding that Melnikoff recruited towards its construction, was an innovation for the small Israeli art scene. From a sculptural standpoint, the statue was connected to the beginnings of the “Caananite” movement in art.

The memorial sculptures erected in Israel up to the beginning of the 1950s, most of which were memorials for the fallen soldiers of the War of Independence, were characterized for the most part by their figurative subjects and elegiac overtones, which were aimed at the emotions of the Zionist Israeli public.[61] The structure of the memorials was designed as spatial theater. The accepted model for the memorial included a wall with a wall covered in stone or marble, the back of which remained unused. On it, the names of the fallen soldiers were engraved. Alongside this was a relief of a wounded soldier or an allegorical description, such as descriptions of lions. A number of memorial sculptures were erected as the central structure on a ceremonial surface meant to be viewed from all sides.[62]

In the design of these memorial sculptures we can see significant differences among the accepted patterns of memory of that period. Хашомер Хатзайыр (The Youth Guard) kibbutzim, for example, erected heroic memorial sculptures, such as the sculptures erected on Kibbutz Яд Мордехай (1951) or Kibbutz Негба (1953), which were expressionist attempts to emphasize the ideological and social connections between art and the presence of public expression. Шеңберінде HaKibbutz Ha’Artzi intimate memorial sculptures were erected, such as the memorial sculpture “Mother and Child”, which Чана Орлофф erected at Kibbutz Эйн Гев (1954) немесе Yechiel Shemi's sculpture on Kibbutz Hasolelim (1954). These sculptures emphasized the private world of the individual and tended toward the abstract.[63]

One of the most famous memorial sculptors during the first decades after the founding of the State of Israel was Натан Рапопорт, who immigrated to Israel in 1950, after he had already erected a memorial sculpture in the Варшава геттосы to the fighters of the Ghetto (1946–1948). Rapoport's many memorial sculptures, erected as memorials on government sites and on sites connected to the War of Independence, were representatives of sculptural expressionism, which took its inspiration from Neoclassicism as well. At Warsaw Ghetto Square at Yad Vashem (1971), Rapoport created a relief entitled “The Last March”, which depicts a group of Jews holding a Torah scroll. To the left of this, Rapoport erected a copy of the sculpture he created for the Warsaw Ghetto. In this way, a “Zionist narrative” of the Holocaust was created, emphasizing the heroism of the victims alongside the mourning.

In contrast to the figurative art which had characterized it earlier, from the 1950s on a growing tendency towards abstraction began to appear in memorial sculpture. At the center of the “Pilots’ Memorial" (1950s), erected by Benjamin Tammuz және Aba Elhanani in the Independence Park in Tel Aviv-Yafo, stands an image of a bird flying above a Tel Aviv seaside cliff. The tendency toward the abstract can also be seen the work by David Palombo, who created reliefs and memorial sculptures for government institutions like the Knesset and Yad Vashem, and in many other works, such as the memorial to Shlomo Ben-Yosef бұл Итжак Данцигер салынған Рош Пина. However, the epitome of this trend toward avoidance of figurative images stands our starkly in the “Monument to the Negev Brigade” (1963–1968) which Дани Караван created on the outskirts of the city of Бершева. The monument was planned as a structure made of exposed concrete occasionally adorned with elements of metaphorical significance. The structure was an attempt to create a physical connection between itself and the desert landscape in which it stands, a connection conceptualized in the way the visitor wanders and views the landscape from within the structure. A mixture of symbolism and abstraction can be found in the “Monument to the Holocaust and National Revival”, erected in Tel Aviv's Рабин алаңы (then “Kings of Israel Square”). Игаэль Тумаркин, creator of the sculpture, used elements that created the symbolic form of an inverted pyramid made of metal, concrete, and glass. In spite of the fact that the glass is supposed to reflect what is happening in this urban space,[64] the monument didn't express the desire for the creation of a new space which would carry on a dialogue with the landscape of the “Land of Israel”. The pyramid sits on a triangular base, painted yellow, reminiscent of the “Mark of Cain”. The two structures together form a Magen David. Tumarkin saw in this form “a prison cell that has been opened and breached. An overturned pyramid, which contains within itself, imprisoned in its base, the confined and the burdensome.”[65] The form of the pyramid shows up in another work of the artists as well. In a late interview with him, Tumarkin confided that the pyramid can be perceived also as the gap between ideology and its enslaved results: “What have we learned since the great pyramids were built 4200 years ago?[...] Do works of forced labor and death liberate?”[66]

In the 1990s memorial sculptures began to be built in a theatrical style, abandoning the abstract. In the “Children’s Memorial” (1987), or the “Yad Vashem Train Car” (1990) by Моше Сафди, or in the Memorial to the victims of “The Israeli Helicopter Disaster” (2008), alongside the use of symbolic forms, we see the trend towards the use of various techniques to intensify the emotional experience of the viewer.

Сипаттамалары

Attitudes toward the realistic depiction of the human body are complex. The birth of Israeli sculpture took place concurrently with the flowering of avantgarde and modernist European art, whose influence on sculpture from the 1930s to the present day is significant. In the 1940s the trend toward primitivism among local artists was dominant. With the appearance of “Canaanite” art we see an expression of the opposite concept of the human body, as part of the image of the landscape of “The Land of Israel.” That same desolate desert landscape became a central motif in many works of art until the 1980s. With regard to materials, we see a small amount of use of stone and marble in traditional techniques of excavation and carving, and a preference for casting and welding. This phenomenon was dominant primarily in the 1950s, as a result of the popularity of the abstract sculpture of the “New Horizons” group. In addition, this sculpture enabled artists to create art on a monumental scale, which was not common in Israeli art until then.

Сондай-ақ қараңыз

Әдебиеттер тізімі

- ^ See, Yona Fischer (Ed.), Art and Art in the Land of Israel in the Nineteenth Century (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1979). [In Hebrew]

- ^ Gideon Ofrat, Sources of the Land of Israel Sculpture, 1906-1939 (Herzliya: Herzliya Museum, 1990). [In Hebrew]

- ^ See, Gideon Efrat, The New Bezalel, 1935-1955 (Jerusalem: Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, 1987) pp. 128-130. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See, Alec Mishory, Behold, Gaze, and See (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2000) pp. 53–55. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] See, Alec Mishory, Behold, Gaze, and See (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2000) p. 51. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Nurit Shilo-Cohen, Schatz’s Bezalel (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1983) pp. 55–68. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] Nurit Shilo-Cohen, Schatz’s Bezalel (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1983) p.98. [In Hebrew]

- ^ About the jewelry design of Raban, see Yael Gilat, “The Ben Shemen Jewelers’ Community, Pioneer in the Work-at-Home Industry: From the Resurrection of the Spirit of the Botega to the Resurrection of the Guilds,” in Art and Crafts, Linkages, and Borders, edited by Nurit Canaan Kedar, (Tel Aviv: The Yolanda and David Katz Art Faculty, Tel Aviv University, 2003), 127–144. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Haim Gamzo compared the sculpture to the image of the Assyrian lion from Khorsabad, found in the collection of the Louvre. See Haim Gamzo, The Art of Sculpture in Israel (Tel Aviv: Mikhlol Publishing House Ltd., 1946) (without page numbers). [In Hebrew]

- ^ see: Yael Gilat, Artists Write the Myth Again: Alexander Zaid’s Memorial and the Works That Followed in its Footsteps, Oranim Academic College Website [In Hebrew] <http://info.oranim.ac.il/home/home.exe/16737/23928?load=T.htm Мұрағатталды 2007-09-28 Wayback Machine >

- ^ Yael Gilat, Artists Write the Myth Again: Alexander Zaid’s Memorial and the Works That Followed in its Footsteps, Oranim Academic College Website [In Hebrew]

- ^ See Haim Gamzo, Chana Orloff (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1968). [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] Her museum exhibitions during those years took place in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1935, and in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Haifa Museum of Art in 1949.

- ^ Haim Gamzo, The Sculptor Ben-Zvi (Tel Aviv: HaZvi Publications, 1955). [In Hebrew]

- ^ Amos Kenan, “Greater Israel,” Yedioth Ahronoth, 19 August 1977. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] The Story of Israeli Art, Benjamin Tammuz, Editor (Jerusalem: Masada Publishing House, 1980), p. 134. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Cited in: Sara Breitberg Semel, “Agripas vs. Nimrod,” Kav, No. 9 (1999). [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] This exhibition is dated according to Gamzo’s critique, which was published on May 2, 1944.

- ^ Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), p. 10. [In Hebrew]

- ^ On the subject of kibbutz pressure, see Gila Blass, New Horizons (Tel Aviv: Papyrus and Reshefim Publishers, 1980), pp. 59–60. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See Gideon Ophrat, “The Secret Canaanism in ‘New Horizons’,” Art Visits [Bikurei omanut], 2005.

- ^ ] Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), pp. 30–31. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: L. Orgad, Dov Feigin (Tel Aviv: The Kibbutz HaMeuhad [The United Kibbutz], 1988), pp. 17–19. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Irit Hadar, Moses Sternschuss (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2001). [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] A similar analysis of the narrative of Israeli sculpture appears in Gideon Ophrat’s article, “The Secret Canaanism” in ‘New Horizons’,” Studio, No. 2 (August, 1989). [In Hebrew] The article appears also in his book, With Their Backs to the Sea: Images of Place in Israeli Art and Literature, Israeli Art (Israeli Art Publishing House, 1990), pp. 322–330.

- ^ David Palombo, үстінде Кнессет website, accessed 16 October 2019

- ^ Gideon Ofrat. "Aharon Bezalel". Aharon Bezalel sculptures. Алынған 16 қазан 2019.

Indeed, the sculptural aesthetics of fire, bearing memories of the Holocaust (at that time finding their principal expression in the sculptures of Palombo)....

- ^ See: Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), p. 76. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Igael Tumarkin, “Danziger in the Eyes of Igael Tumarkin,” Studio, No. 76 (October–November 1996), pp. 21–23. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Ginton, Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), p. 28. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Ginton, Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 32–36. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Yona Fischer , in: Itzhak Danziger, Place (Tel Aviv: Ha Kibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House, 1982. (The article is untitled and preceded by the following quotation: “Art precedes science.” The pages in the book are unnumbered). [In Hebrew]

- ^ From "Rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry, Israel Museum, 1972, " in: Yona Fischer, in Itzhak Danziger, Place (Tel Aviv: Ha Kibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House, 1982. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Itzhak Danziger, The Project for the Memorial to the Fallen Soldiers of the Egoz Commando Unit. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] Amnon Barzel, “Landscape as an Artistic Creation” (Interview with Itzhak Danziger), Haaretz (July 27, 1977). [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Ginton Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 88–89. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Yigal Zalmona, Onward: The East in Israeli Art (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1998), pp. 82–83. For documentation of much of Danziger’s sculptural activity, see Igael Tumarkin, Trees, Stones, and Fabrics in the Wind (Tel Aviv: Masada Publishing House, 1981. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] See: The Story of Israeli Art, Benjamin Tammuz, Editor (Jerusalem: Masada Publishing House, 1980), pp. 238–240. Also Gideon Efrat, Abraham Ofek House (Kibbutz Ein Harod, Haim Atar Museum of Art, 1986), primarily pp. 136–148. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] Pierre Restany, Kadishman (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1996), pp. 43-48. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Pierre Restany, Kadishman (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1996), p. 127. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Ruti Director, “When Politics Becomes Kitsch,” Studio, no. 92 (April 1998), pp. 28–33.

- ^ See: Amnon Barzel, Israel: The 1980 Biennale (Jerusalem: Ministry of Education, 1980). [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Video Zero: Written on the Body – A Live Transmission, the Screened Image – the First Decade, edited by Ilana Tannenbaum (Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, 2006), p. 48, pp. 70–71. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Video Zero: Written on the Body -- A Live Transmission, the Screened Image – the First Decade, edited by Ilana Tannenbaum (Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, 2006) pp. 35–36. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Jonathan Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 142–151. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Қараңыз: Бейне нөл: денеде жазылған - тікелей эфирде, экрандық сурет - бірінші онжылдық, редакциялаған Илана Танненбаум (Хайфа: Хайфа өнер мұражайы, 2006), б. 43. [еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Ирит Сеголи, «Менің Қызылым - сенің қымбатты қаның», Студия, No76 (қазан-қараша 1996 ж.), 38–39 бб. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Гидеон Эфрат, «Заттың жүрегі», Гидеон Гечтман: Шығармалары 1971-1986, 1986 жылдың күзі, нөмірсіз. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Нета Гал-Ацмон, «Түпнұсқа және имитация циклдары: 1973-2003 жж.», Гедеон Гечтман, Хедва, Гидеон және қалғандарында (Тель-Авив: Суретшілер мен мүсіншілер қауымдастығы) (нөмірсіз борпылдақ папка). [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Сарит Шапира, бір уақытта бір нәрсе (Иерусалим: Израиль мұражайы, 2007), б. 21. [еврей тілінде]

- ^ Нахум Тевет «Check-Post» көрмесінде (Хайфа өнер мұражайының сайты) қараңыз.

- ^ Дрора Думаниді «Check-Post» көрмесінде қараңыз (Хайфа өнер мұражайының сайты).

- ^ Қараңыз: Итамар Леви, «Жоғары профиль», Студия: Өнер журналы, № 111 (2000 ж. Ақпан), 38-45 б. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Zik тобы: жиырма жылдық жұмыс, редакторы Дафна Бен-Шаул (Иерусалим: Кетер баспасы, 2005). [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ ] Қараңыз: Galia Bar Or, «Пародоксикалық кеңістік», Студия, № 109 (қараша - желтоқсан 1999), 45-53 бб. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: «Мәжбүрлі иммигрант», Ynet веб-сайты: http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-3476177,00.html [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Дэвид Шварбер, Ифча Мистабра: Ғибадатхана мәдениеті және қазіргі заманғы Израиль өнері (Рамат Ган: Бар Илан университеті), 46–47 бб. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Орнату туралы құжаттаманы мына жерден қараңыз: «Кешкі көйлек» және онымен байланысты YouTube-тегі бейне.

- ^ Қараңыз: Левия Стерн, «Дора туралы әңгімелер», Студия: Журнал, № 91 (наурыз 1998), 34-37 бб. [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Амитай Мендельсон, «Ашылу және жабылу көзілдірігі: Израильдегі өнер туралы дүрсілдер, 1998-2007», Нақты уақыт (Иерусалим: Израиль мұражайы, 2008). [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Гидеон Эфрат, «1950-ші жылдардағы диалектика: Гегемония және көпжақтылық», Гидон Эфрат және Галия Бар Ор, Бірінші онжылдық: Гегемония және көпсалылық (Киббутц Эйн Харод, Хаим Атар өнер мұражайы, 2008), б. 18. [еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Авнер Бен-Амос, «Жады мен өлім театры: Израильдегі ескерткіштер мен салтанаттар», Дрора Думани, барлық жерде: Израильдің пейзажы мемориалымен (Тель-Авив: Харгол, 2002). [Еврей тілінде]

- ^ Қараңыз: Галия Бар Ор, «Әмбебап және халықаралық: Бірінші онжылдықтағы Кибуттің өнері», Гидеон Эфрат және Галия Бар Ор, Бірінші онжылдық: Гегемония және көпжандылық (Киббутц Эйн Харод, Хаим Атар өнер мұражайы, 2008) , б. 88. [еврей тілінде]

- ^ Йигал Тумаркин, «Холокост пен жаңғыру ескерткіші», Тумаркинде (Тель-Авив: Масада баспасы, 1991 (нөмірлері жоқ беттер)

- ^ ] Йигал Тумаркин, «Холокост пен жаңғыру ескерткіші», Тумаркинде (Тель-Авив: Масада баспасы, 1991 (нөмірлері жоқ беттер)

- ^ Маркус Михал, Игал Тумаркиннің кең уақытында.